website slowly developing; latest update 17th December 2025

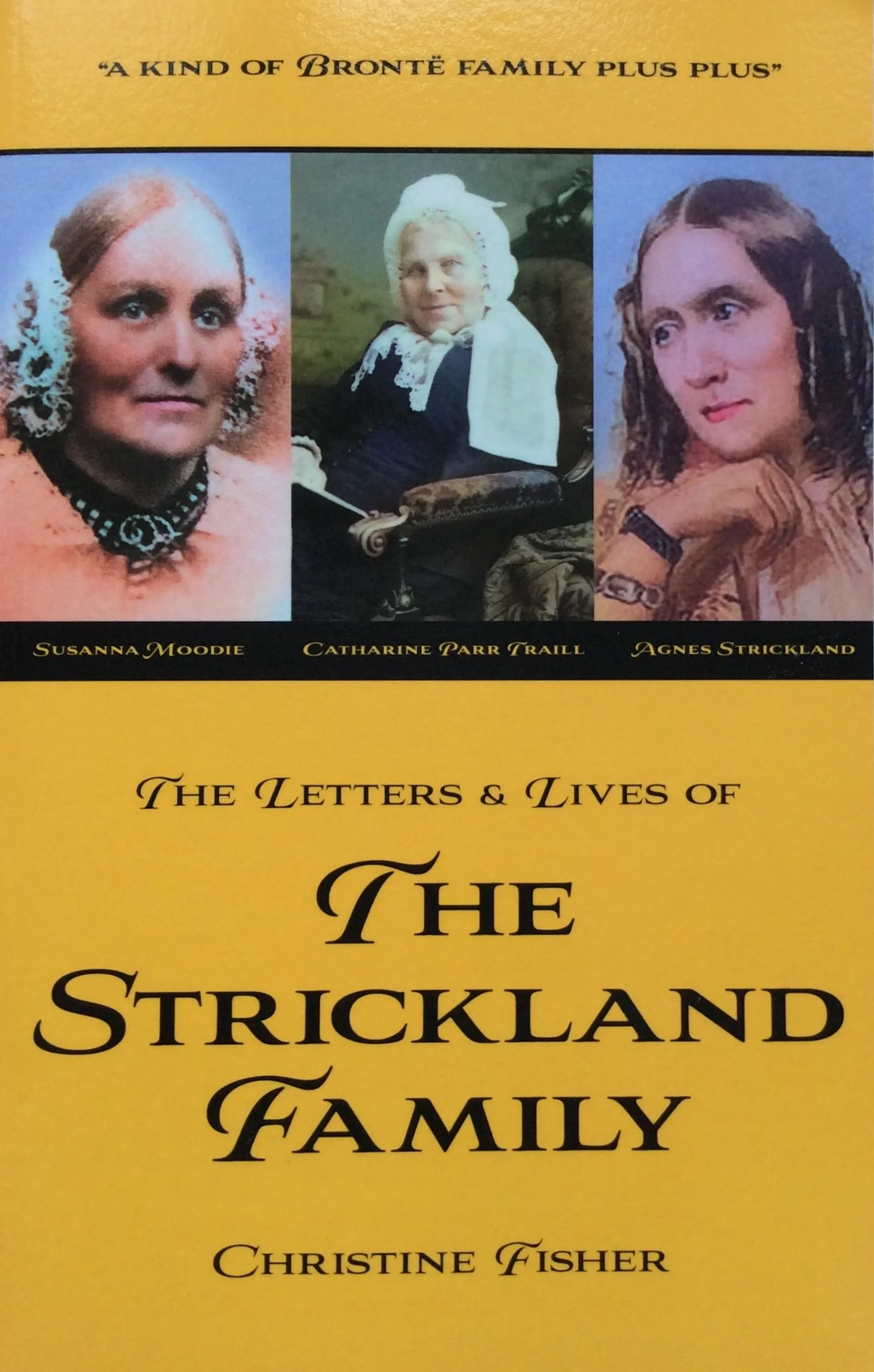

This Strickland family had literary talents to outshine the Bronte family - and much more besides. Their letters, journals and writing combine to give a fascinating insight into life in 19th century Canada and England.

paperback ISBN 978-1-83975-157-8 available from any book shop or via Amazon where a preview is available; eBook ISBN 978-1-80381-155-0

Agnes Strickland (1796-1874). “Lives of the Queens of England” introduced a new type of history book. Enjoyable to read as well as factually correct. Agnes was an international celebrity who succeeded in keeping secret that her sister Elizabeth Strickland (1794-1875) was often her co-writer but insisted on anonymity. They both were born, lived and died in England.

Susanna Moodie (1803-1885). Poet and novelist, most famous for “Roughing It in the Bush”, her dramatised recollections of her early life in Canada after emigrating from England with her husband and young child in 1832.

Catharine Parr Traill (1802-1899) combined writing for children with serious botanical works such as “Studies of Plant Life in Canada”. She emigrated from England to Canada in 1832 with her husband who was unsuited to the hard physical labour of a pioneer farmer. She always needed financial and practical help from her sisters Agnes, Jane and Sarah in England and from her brother Sam and his family in Canada. ‘Traill College’ in a Canadian university is named in her memory.

Sam Strickland (1805-1867) emigrated to Canada aged 19. He carved out his farm from dense forest and was successful both as a farmer and a businessman. He is commemorated in Lakefield, Ontario - where he was one of the original settlers. His sisters Catharine and Susanna are also commemorated there.

Jane Margaret Strickland (1800-1888) poor health and caring for their ageing mother restricted her life. She earned a living in various ways - editing Christmas annuals, proof-reading for her sisters, plus writing a detailed history of Rome, a romantic novel and a biography of Agnes Strickland. She lived most of her life in Suffolk, England.

Sarah Strickland Gwillym (1798-1890) was the beauty of the family. She married and was widowed twice. Her face is familiar to many Canadians because a portrait of her as a young woman was given much publicity in the mistaken belief that it was a portrait of her sister Catharine. Her second husband, a vicar in Lancashire, left her a lifetime interest in his considerable assets and she gave financial support to other members of her family, particularly to Catharine. She lived and died in England.

Captain Tom Strickland (1807-1874) joined the merchant navy aged 14. He became a Master Mariner, and was captain of sailing ships that took him to places as far afield as India, Australia, the United States and Peru. His wife sailed with him for many years and several of his children were born at sea. When not at sea, he lived in England.